As I mentioned in the last article, I returned from Muscle Camp a changed person. I had just lived out a dream.

My goal had always been to get to the bodybuilding Mecca on my own, and up until Muscle Camp I’d naïvely thought the only way to do that was to win an actual pro card and get noticed or at least compete down there.

But my heart was never really in competing after the first few contests. For me, bodybuilding wasn’t about extreme dieting to “beat” other people for a first-place trophy. For me bodybuilding was about 1) my fascination with the human body and what it could do, and 2) physique as performance art. I used to say that I didn’t even consider myself “a bodybuilder.” I considered myself an athlete… who was currently doing bodybuilding.

To put it another way, for me bodybuilding was a lot like golf. Or, as The Legend of Bagger Vance put it: “it is a game that can’t really be won, only played.” The only measure for that kind of thing is your own level of progress; all the rest is smoke and mirrors to my mind. The contests were really just a means to an end.

So, after having been to Muscle Camp, my perspective shifted. I had just trained with legends. I had been made to feel accepted by legends. The idea of competing in order to prove something seemed even more unnecessary.

But my love for training and all was still there.

When I returned home there was immediate clarity and this gave me immediate direction as well.

We call these “light bulb moments.” My direction was clear.

In 1987, the 81-lb. difference between then and my first contest in 1983 was unheard of. It helped gain me a reputation in the bodybuilding community. The fact that I had the academic thing going gained me some publicity outside the bodybuilding community, and it led, of course, to Muscle Camp.

By 1989 I was honing my methods. More and more, I’d started to use what I’d learned. I even taught some of it at Muscle Camp, and after that experience, I felt confident as an expert. When I returned home and compared myself to some of the members of the peanut gallery, it was night and day. They just weren’t in the same league.

Before Muscle Camp I’d had more doubts about sharing my knowledge. Now, that was gone. And I felt that if I helped other competitors, their results would be as eye-opening as mine had been.

The lesson here has driven my career to this day:

Using your real, authentic expertise for helping other people achieve their goals is not only very lucrative — it’s incredibly fulfilling.

My return from Muscle Camp is when I really immersed myself in one-on-one Coaching.

Diving Into One-on-One Coaching

My real foray into one-on-one Coaching (mostly for bodybuilders back then, although now I work with both bodybuilders and real-world people too) was at a time when very few others were doing it in a serious way, and as a true business.

I began by coaching competitors, and I did it when very few people were doing it — and the ones who were doing it really had no idea what they were doing. Really, they just told their so-called clients to do whatever they were doing. This still exists today, but it’s not what real capital-C Coaching is all about.

I also did something else that the other coaches weren’t doing. I charged an upfront fee and a monthly fee, but I also asked my clients for one more thing: when they were introduced on stage, they have the contest M.C. announce that they were trained and Coached by Scott Abel.

No one else was doing this. It seemed like a bold move and to some others it was perceived as brazen.

But then again, my clients just plain looked more advanced than a lot of the competition. At one contest, my clients won every weight class, male and female, and in many of the categories the first-, second- and third-place winners were all my clients.

It didn’t take long for my reputation to spread and then for me to be recognized nationally. By 1991–92, I was able to quit social work entirely.

As word spread of my clients’ success, people began looking for my “secret.” No one could figure out why my clients looked so advanced and why they were doing so well. Everyone was looking for my secret as though it was something that could be reduced to one or two small details or circumstances.

But the secret was there were no secrets. (Hint: It was capital-C Coaching.) Most people in the industry just couldn’t grasp the idea of a comprehensive and individualized approach. They were used to what I now call an “outside-in” approach to training and diet.

For example, most people were still just doing workouts while I was writing programs — and then individualizing them. So whereas most coaches were just assigning a collection of workouts that happened to have worked well for them, I was doing physique and lifestyle assessments, and adjusting things based stress, previous athletic experience, and a bunch of other factors. Back then, no one else was really taking this kind holistic approach.

Other coaches were about assigning “their” diet and workouts to all their clients. I was interested in Coaching the whole person.

Other coaches were dieting their competitors by making changes according to some arbitrary number of “weeks out” before the contest. I was adjusting based on calorie needs and expenditures (though even back then we didn’t count calories much). My methods then were crude compared to now, but they were light years ahead of what everyone else considered contest-prep to be all about.

I made changes to diets and training protocols only if and when a competitor’s biofeedback determined a change to be in order. For example, if their physiques weren’t changing and tightening up, or if their physiques were changing too quickly, then I adjusted diet and training accordingly.

In other words, client biofeedback is what separated my approach from everyone else’. I was all about this “inside-out” approach. Put simply, this approach means that the individual biofeedback of your own body is the most reliable information there is, so you stick to tweaking diet or training protocols according to that and only that. You don’t do it because of some external number. You don’t do it because of some pre-set formula. You do it only if biofeedback demands it.

As an example, I once gave a National level competitor five days completely off diet and training when they were only four or five weeks out from their contest. Everyone thought I was nuts. She came back from her break, we altered her diet a bit, and she went in to Nationals and won and won her pro card as well.

A Labor of Love

Once I quit social work I was in demand, but I also made myself visible everywhere. I would sometimes be in three-to-five cities in a single day. I was often on the road by 4:00 a.m., heading East or West, then training in some other city by 6:00 a.m. or so — then see a few clients, shake a few hands — then off to the next city. I could never keep up that kind of pace now.

A couple gyms even offered me my own office, if I’d stay and workout regularly at their gym. I pretty much never had to pay for gym memberships.

Backlash

In the competition world, I started to receive big amounts of backlash — and I wasn’t ready for it.

I had clients who loved me, but there were people who hated me as well. At one point, rules were introduced to ban me from the backstage areas of some contests. It was felt my presence gave an unfair advantage to my competitors and intimidated other competitors. Let me add, though, that other wannabe coaches and trainers were still allowed backstage. Oh, and some these other coaches just happened to be a part of the executive committees that made these rules.

This kind of thing didn’t stop my clients from dominating.

Soon, the magazines were calling, and Bob Kennedy from Muscle Mag International took a liking to me. I felt a mutual respect, and I clicked with him in a similar way I'd done with Bill Pearl and Joe Gold. This resulted in a lot more exposure. This led to a lot more business, more of a celebrity status, and—of course—even more backlash.

Bob actually showed me letters written to him complaining that I was in his magazine so much when I didn’t even compete. But he also showed me letters from readers and subscribers who couldn’t care less about competitions, and they wanted more “Scott Abel expertise.” This actually gave me goose bumps at the time.

The exposure I got in the magazines, especially Muscle Mag, was huge for my business. With that kidn of exposure, you don’t have to pursue clients; they pursue you.

Although I was in other magazines, Muscle Mag alone went out to over 20-25 countries at the time, so my Coaching business went from national to international.

By this point, my coaching and training methods were transforming into well-honed diet and training methodologies that were helping people all over the world achieve their goals. This became true for competitors and non-competitors alike, because I quickly learned that a lot of people outside the bodybuilding world nonetheless devoured the magazines.

Helping others is what had drawn me originally to social work, but the fitness world and coaching let me do it on a much bigger scale.

The Changing Steroid World

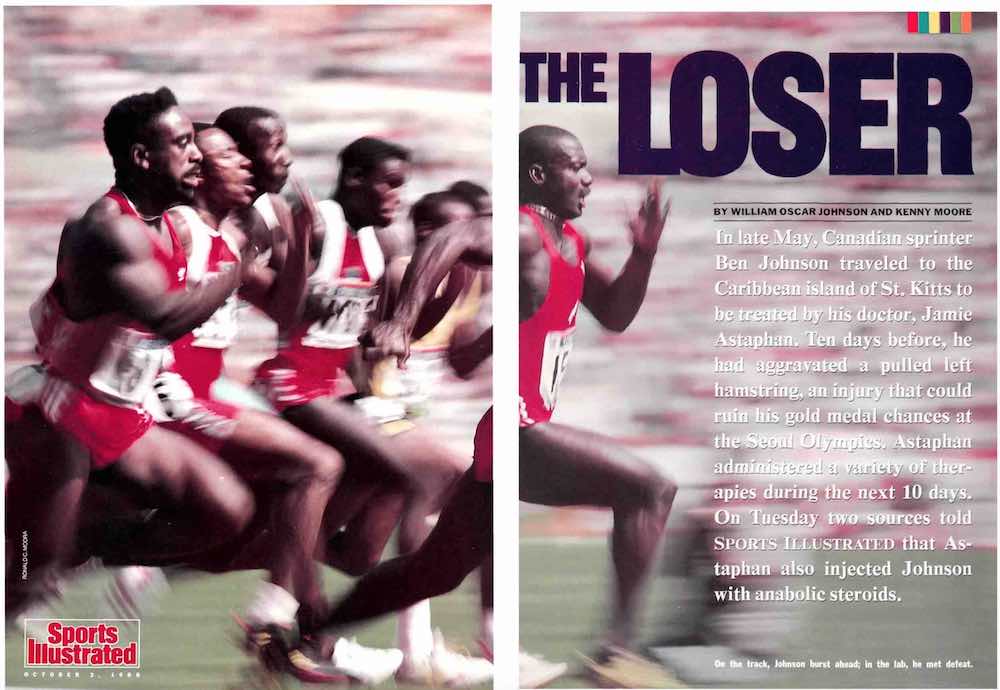

Keep in mind that during this time, the bodybuilding world itself was in total upheaval. The Ben Johnson shenanigans of 1988 and the government Dubin Inquiry made steroids front page news. It also pushed steroids completely underground and this was NOT a good thing. (More about that in a later article.)

Ben Johnson in Sports Illustrated, October 3, 1988.

I mentioned in the 80s you could get steroids from local doctors. Well, by the early to mid-90s the most reliable sources for anabolic steroids were… vets.

As in, veterinarians.

Yep, that’s right — and no one blinked over it!

If you knew someone who owned horses, or you could make friends “at the track,” then not only could you procure all the steroids and other drugs you wanted, you could create a lucrative little cottage industry for yourself as well.

Even various tack shops sold steroids like testosterone, equipoise, or clenbuterol right on their supply shelves, right out in the open. You could purchase cases of these drugs if you want. In the bodybuilding world, no one thought that any of this made you a drug dealer, even though everyone was perfectly aware that this kind of thing was totally illegal, especially given all the coverage the mainstream media was devoting to the topic.

A Little Pharmacology 101

The bodybuilding drug subculture was being forced underground at the very same time as pharmaceutical use was fast becoming an arms-race.

The bodybuilding drug subculture was being forced underground at the very same time as pharmaceutical use was fast becoming an arms-race.

Guys took as many drugs as they could afford and in as high of a dose as they could afford. Side effects like acne vulgaris and serious abscesses from injections were becoming common place.

In pharmacology, injectable drugs are almost always more potent than their oral counterparts, even at equal doses. Anyone who has ever had injectable gravol over oral gravol, or injectable morphine over oral morphine knows what I mean.

Well, think about this:

In my 1986 bodybuilding retrospective article, I mentioned that the doctor gave me a prescription for Winstrol tabs at 2-mg strength.

Well, the injectable Winstrol-V — the kind you give to horses — was 50 mgs per ml.

This meant that one cc of veterinary Winstrol-V was 25 times stronger than the oral dose I was given—and it was injectable. This kind of thing would be like going from taking two extra-strength Tylenol for a headache to grinding up 25 tablets and taking that instead. Or going from two extra-strength Tylenol to injecting heroin.

That’s is the kind of difference we’re talking about here.

Bodybuilding was fast becoming an underground drug sub-culture. And like any underground sub-culture, it started to attract the lowest and worst kinds of people.

Whatever purity or innocence the bodybuilding game had originally possessed was now more or less gone — evaporated into some pharmaceutical ether. You either pursued bigger and bigger or you got out of it. There was no in-between like there now is today.

It was adapt — or die. And just like my attitude toward diet and training, I immersed myself in becoming as expert as I could in all elements of pharmaceutical use to alter physiques.

Conclusion

I still hear about people willing to pay others to find out about Scott Abel’s drug recipes. But they just couldn’t figure it out: it’s not the recipe, it’s the chef.

I was working as a master chef, always stopping to taste and tweaking things as necessary. Most wannabe coaches were effectively just reading the directions on the back of the label, ending up with a pretty good result at best.

The success continued, but so did the jealousy and the hate, and I admit that I did not handle that part well or maturely most of the time.

My clients still dominated competition. By having the opportunity to Coach dozens and dozens of different people from both genders and across age groups, at varying levels of experience, development and bodyfat, I was in the best classroom in the world to teach myself how to read and gauge the individual differences that mattered in order to help people at all levels achieve extremely impressive results.

And that is what I would hang my hat on for decades to come.

To be continued…