This is a guest blog by Perry Mykleby:

Meat head. Iron head. Muscle head. Those are terms used to describe guys (mostly) who are longer on muscle than brains.

In recent years, I’ve learned there’s a lot more head involved in building muscle than I understood originally, and the longer I’m at it, the more I’ve realized that intelligence and neuroscience plays almost as big a role in muscle development as do the muscles themselves.

I got a personal lesson on this in 2004. I woke up one day with a searing pain between my shoulder blades that would’t go away for weeks. So, like any good American male, I ignored it, until I couldn’t any more. The tortuous path of the healthcare system led me to the office of one of the baddest-ass neurosurgeons on the planet. (I won’t mention his name, but he’s done spinal cord surgery on some names you’d recognize.) After he looked at my MRI, he asked me something I don’t think I’ll ever forget. It went something like this:

Surgeon: “How did you hurt your cord?”

Me: “Exsqueeze me? Hurt my cord?? I was thinking pinched nerve.”

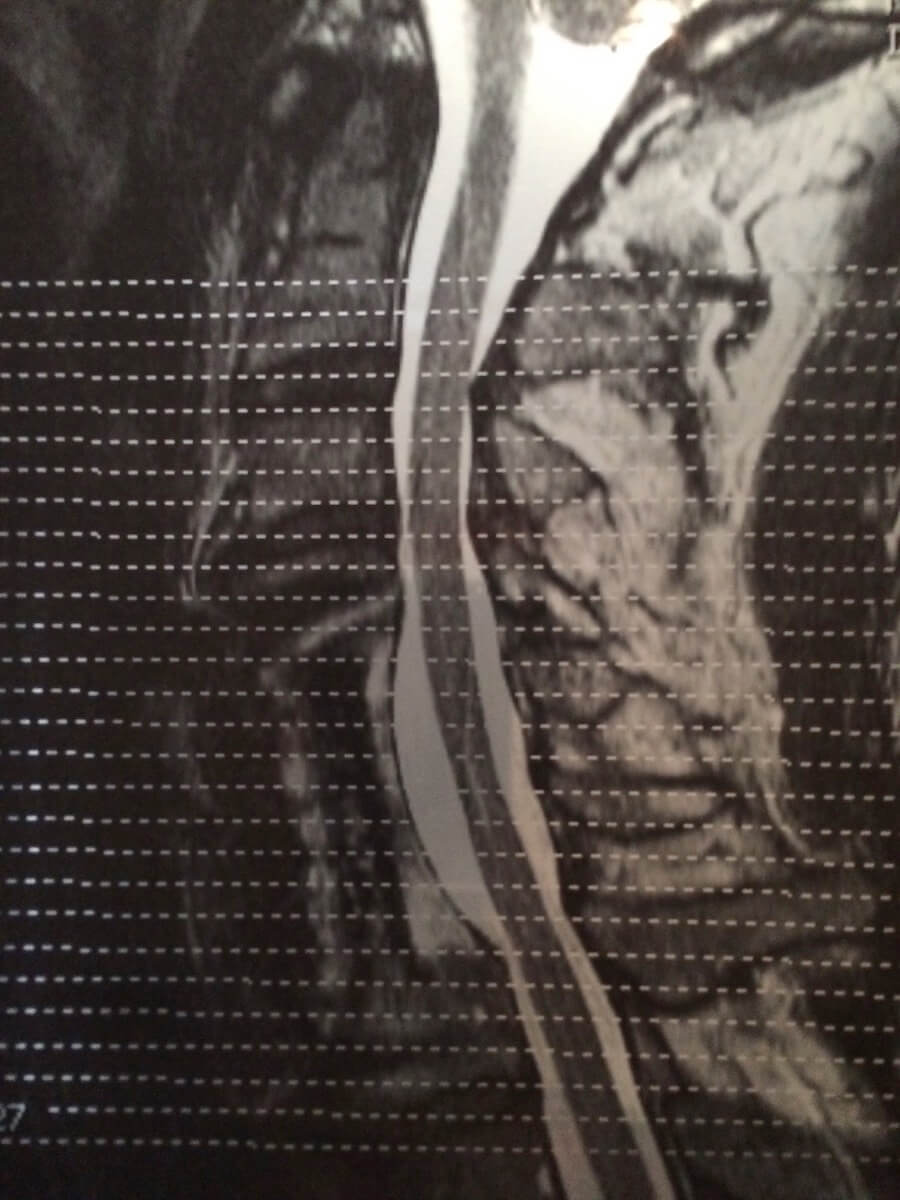

Surgeon: “Well, yes. It’s a nerve. THE nerve. You have a spinal cord injury in your neck. Two bones are pressing against the cord. [Points to the injury on the MRI.] You have two choices. We can do surgery to repair it; or, you can let it go. But, you’ll lose the use of your right arm…then your right leg…then your left arm, and then the left leg. And then you’ll spend the rest of you your life in a [wheel]chair paralyzed from the neck down.”

Me: “Hmmmm. Let me think about that.”

I didn’t really say that. I said something more like, “Busy later?”

He went on to explain that the two cervical vertebrae wedged up against my spinal cord, and that it was a very old injury that was just now symptomatic. (My car was rear-ended at a stand-still in 1983 by someone traveling ~45 mph.) The surgeon said the bones would need to be removed in a procedure called a corpectomy. A corpectomy is like a discectomy on steroids. A disc procedure takes a couple hours. A corpectomy is an all-day event. They remove the bones, the disc material—everything—and span the gap with bone they take from elsewhere, plus some expensive titanium hardware not available at Home Depot. The surgeon explained that my spinal cord showed “signal loss”, sort of like a short circuit in an electrical cable, which explained why my right arm was hurting, tingling, numb, and getting weaker (and smaller) by the week.

By the time my surgery date rolled around, I couldn’t cut my food, tie my shoes or brush my teeth with my right hand. I couldn’t do a dumbbell triceps extension with even 5 lbs. Shaking hands was an embarrassment.

MRI of my neck. Front is to the left. The long skinny gray thing in the middle is my cord. The cord floats in a tube called the dura which appears white in the MRI. You can see the ballooning out where they removed the neck bones. The vertical black, rod-looking thing is a piece of leg bone where the neck bones and disks once were.

The 13-hour surgery removed the offending vertebrae and replaced them with a leg bone graft and the titanium appliances anteriorly and posteriorly. I spent 90 days in a hard plastic neck brace, with no driving, and very limited activity in general. “Pick up nothing heavier than a newspaper or coffee cut for the first two weeks.” After that, I was allowed to take walks, which I did with enthusiasm.

When the neurosurgeon later told me I could start back in the gym, I could've kissed him. But I now had to come back from not just a lay-off, but atrophy the cord injury caused. My once beefy right hand now looked more like a chicken foot. My right triceps was now smaller, with an area that would not flex no matter how hard I tried.

Still in the hard plastic neck brace, my best buddy chauffeured my now-skinnier, lop-sided self to the gym so I could do the short list of surgeon-approved exercises: dumbbell side laterals, dumbbell curls, machine presses and machine rows. Light weights. Lots of reps. I don’t even think I counted. I was simply so happy to be pain-free and able to control my arm. Just watching the weights go up and down brought joy, and the smoother and more rhythmic, the more joyful.

And then I noticed a funny thing happening. Using those light weights, lots of reps and intense concentration, I got shape and definition I’d never had before.

In my new physical reality, form had become more important than ever to avoid re-injury, and that meant using my brain as much as my muscles. I had to “think into” the muscles, concentrating on every inch of every rep of every set. Enter innervation training.

I happened across the term “innervation” in Scott's Abel Body Expert videos shortly after that episode. In those, he spoke about innervation training and it resonated. I first heard the term “innervation” back in 1982 at Dan Canales' gym. Dan’s gym was a hard-core lifting space that Dan—a powerlifter—had installed on first floor of the vacated Phi Gamma Delta frat house at North Texas State. He equipped it with expensive, competition-legal barbells, Metro Athletic Club dumbbells, and complemented it all with some of the best homemade machines I ever used. Membership was invitation-only, and training for competition was mandatory. Dan and I were in the gym on a Saturday when I noticed him using extremely light weights, and ultra-conservative form. This particular day he was benching, bar only, practicing lowering the bar to his chest, pausing, then exploding it upward, just as he would do in a powerlifting meet. He explained it was “innervation day,” where he was training his brain and his neuromuscular pathways to “memorize” the movement.

Fast-forward a quarter century, when I heard innervation again in those Abel videos, it caught my ear. Between that resonant memory of Dan’s gym, Scott’s methods, and my own experience, my whole approach to lifting changed. Although my right hand is still bony, the triceps is smaller and my right shoulder droops a couple of inches, my right arm is now strong again—even stronger on some exercises.

Those episodes and my post-surgical reality drilled home a few lessons that helped me regain and even surpass the physique I had twenty years ago. I thought I’d share a few “crunchy nuggets” of information that have helped me, and may help someone else, so here goes:

1. The weight should be an extension of your body. Become one with the weight. Picture the lifter and the weight, not the lifter versus the weight. The lifter becomes the engine that makes the iron move, all part of one unified machine. A few challenge questions: Is that “machine” moving like it’s fit-for-purpose, rhythmic, well-tuned and sturdy? Is it traveling the proper distance? Or is it jerking like a car with transmission problems? Are you moving the weight or is it moving you? What are the sounds? A crescendo of crashes, or rhythmic touching and softly clinking…or making no sound at all? Are you moving the iron, or is it moving you? These are essentials of pumping iron.

This leads me to the next point.

2. Training for hypertrophy is as much mental and intellectual as it is physical. I'll borrow a term I've heard Scott use: selective activation of agonists. To me, that means keen focus on contracting the muscles being isolated…thinking into the muscle. Using side laterals as an example, consciously tense the deltoid against the weight before moving it, so that it’s pre-loaded. Then focus the mind on the deltoid strongly contracting, moving the entire arm and weight without using the arm for locomotion. If the arm or any other body part starts to aid in the locomotion, the weight's too heavy for true isolation.

3. Unrelenting tension. For muscles to be loaded as they must for hypertrophy, they must be under tension. Otherwise, it decreases total time under load. That means maintaining tension in the muscle throughout the full range of motion. Think of training a muscle like stretching a rubber band. Never begin with the band relaxed, and never letting go at any time during the movement. It should always be under tension, and the movement is just a matter of stretching it back and forth. My first lifting mentor, Tim Jackson, used the term “squeeze” to describe the feeling. Flex upward, control downward.

Releasing between reps is seldom more evident that on lat pull-downs. You know what I'm talking about. You know who they are. They pull down hard (sometimes all the way), then let the weight carry their arms upward only to relax at the top. Then comes the inevitable downward torso jerk to reinitiate the next pull. Sloppy. Pointless. Risks unnecessary joint wear and tear. Reduces the total time under load. In summary, the set is pretty much a complete waste of time and effort. (And if I can be selfish, if I'm waiting to use that machine, you're wasting my time too.)

4. Muscles can’t do math. Choose a weight you can lift with flawless form through the entire range of motion for the entire set. I never felt as liberated in my workouts as when I learned that I didn't need to be hucking around heavy weights in order to grow muscle. That doesn't mean lifting is effortless. It does however mean freedom to concentrate on the muscles you're isolating. Every set should have smooth rhythm. You should be able to put music to it. The benefits are added enjoyment in every workout, where a constant quest is performance of the perfect set: the intended muscles doing all the work, completely isolated, and completely in control.

5. Know when to say “when.” In Texas we had a saying: Sometimes you eat the bear; sometimes the bear eats you; and sometimes it doesn't even pay to go into the woods. Some days, I don’t go into the woods. Physique After 50 drove home the point of longevity. I'd rather spare myself injury by missing the gym today, than try to be a hero and miss six weeks or more. I'm learning to more accurately read my own body, recognizing when sore is too sore. Delayed onset muscle soreness or burning is a pretty good sign that I just need to take the day off or do something low impact like taking a long walk, or remove the ailing body part from that day’s routine. On those “sore” days, if I'm still hurting after a warm-up and general preparation, I'll pack the bag and come back the next day.

These same lessons learned from the cord injury informed my training after a left total hip replacement several years later, made necessary by degenerative osteoarthritis.

Strictly-performed exercises (often single side) with intense mental concentration, focused contraction and pumping rhythm have provided what my body needed to recover from both the hip and neck injuries. In short, at 57, even with the injuries, I’m more a muscle head than I ever was before.