In my previous article on the Squat I argued that the squat is the number one, most effective exercise in existence, all things considered.

However, for various reasons lots of people cannot do the normal barbell back squat, so other variations of the squat need to be used. I myself had to give up the traditional low bar barbell back squat because I could no longer hold a bar on my back due to restricted shoulder mobility. Later on in my career I also had two discs removed from my low back, which by itself would have made the traditional low bar barbell back squat too risky for me because of spinal compression risk factors.

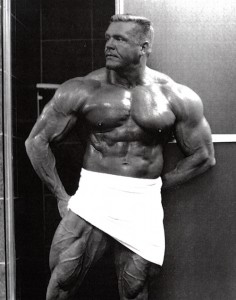

The Front Squat became my central focus in leg training, and it helped me develop very advanced thigh sweep that had previously been missing from my overall development.

Focusing on the front squat also forced very deep lines and cuts and separation within all the muscles of my quads. An added bonus was more noticeable abs definition, along with serratus and intercostal effects. This is because of the position of holding the bar in the front squat position (which activates the anterior chain) while performing an variety of rep schemes over time.

The front squat uses a different movement pattern than the conventional back squat does. In the conventional back squat there is a lot of “hip drive.” But in the front squat, the hips are no longer the central feature.

When executing a front squat, your knees and chest position are the key things to mentally “lock into focus” during your reps. A low bar barbell back squat — when done correctly — will follow a back angle of somewhere between 30 and 50 degrees (as opposed to 90 degrees if you were standing straight). But with the front squat, the bar sits higher up on the body, and the bar sits in the anterior chain with elbows up and with the bar trapped in place on top of the anterior delts. This is why the abs/core are so involved in front squats. From this position the back angle is practically vertical to the floor.

What this means is that “hip drive” doesn’t work the same in the front squat at all although it does “contribute” to the movement. And because there's less hip drive, the front squat is more of a “pure” quadriceps exercise in that regard, with the hamstrings and hips contributing less work than glutes and quads.

A simpler way of saying this in general terms is that between the front squat and the low-bar back squat, the position of the bar (anterior plane or posterior plane respectively) determines the most efficient way to drive out of the pocket.

Since the front squat places the knees so much further forward than with the back squat, the hamstrings are not nearly as involved in the resulting hip extension coming out of the bottom position of the front squat. This places the quadriceps in the position to do most of the work and take on most of the load. The load is not as “spread out” as it is in the low-bar barbell back squat.

Furthermore, the load on the lumbar spine in the front squat is far friendlier than in the traditional low-bar barbell back squat, though this is assuming that the upper erectors maintain position throughout the entire range of motion of each rep. Because of the positioning of the bar, and the fact that the hamstrings isn't taking on as much of the load, lighter loads just naturally need to be used in the front squat relative to the back squat — but it's a fair trade-off, considering you get much more efficient quadriceps overload. This is another reason why yet again “how much you lift” is really just an incidental consideration in the overall picture of “targeted” effects and responses when training for muscle development.

Another benefit of the front squat is noticeable glute involvement. This is the result of concentrated eccentric force on the glutes without the help and contribution of the hamstrings as would take place in the traditional low-bar barbell back squat and the “hip drive” sequence it creates. This is useful to know for practical cosmetic reasons. For instance… ladies looking for that “lifted” glutes look (i.e. that round but tighter and athletic looking glutes) you would do well to enlist full front squats in your training, along with other squat variations like Bulgarian Split Squats, and DB squats with DB’s hanging at your side (and of course lunges and their many variations as well).

The truth is that because of bar position the front squat doesn’t load the hamstrings very much and not as well as does the traditional barbell back squat. So, if you are just learning to workout and exercise and/or if you are targeting the posterior chain more specifically, than the traditional low-bar barbell back squat is the better choice. But if you want to isolate the quads and glutes, the front squat's the way to go.

The front squat has virtually the same generous metabolic effects as the traditional barbell back squat (but without the same spinal compression forces and risks). This makes it a more versatile exercise for metabolic work, and a good exercise to use in exercise complexes, since the low back is less likely to spasm or tighten up. A good example of using the front squat in this way is my Abel Body “Leg 30’s” protocol: a grueling metabolic and targeted leg training sequence for higher-end performance.

Front Squat Caveats

Having said all this, let’s not lose sight of the fact that the front squat, just like the traditional low-bar barbell back squat, is still an advanced exercise and requires learning “technique” not as much by studying it, as by doing it. It will take time to get used to doing the front squat efficiently without having to think about it while you are doing it. Most advanced exercises are like this.

Even with that in mind, some people have anatomical proportions that make front squats problematic. For instance, a short torso with long legs (or long limbs in general) is not a very efficient anatomical combination for being able to maintain good vertical form during the execution of the front squat from rep to rep. Another limitation, and the one I witness most often, is a trainee with very narrow clavicles or a complete lack of development in the shoulder area will have trouble keeping the bar in place on the shoulders. The more you have to think about securing the bar in place, the less concentration you will be able to put into the quads.

As with any exercise of this nature, what is most apparent in an exercise like the front squat, is that anthropometry (individual structure and leverage systems) will always affect a trainee’s ability to learn and execute a movement efficiently and as intended. This is most true of barbell exercises. If you are a trainer, you need to keep this in mind and remember the exercise (and the program) should fit the client, not the other way around.

Yes, this means DBs are often better tools for certain exercises for certain clients. Dumbbell squats, with DB’s hanging at your sides, are a great way to teach and train ample hip drive and hip extension (as you get in the front squat) but like the front squat they pretty much negate any spinal compression concerns as well. For anyone with back or shoulder issues, this means you don’t have to give up the squat… the best whole body exercise there is.