I believe there can be tremendous value in nostalgia. Nostalgia can bring mixed feelings, and yes, it is possible to spend too much time in it—but I really believe there can be tremendous value in it.

Recently, I discovered some old photos.

With some help, I was able to digitalize them, so I can now share them with you. Sometimes a picture really is worth a thousand words, but several pictures end up taking you on a bitter-sweet journey to the spirit of what once was.

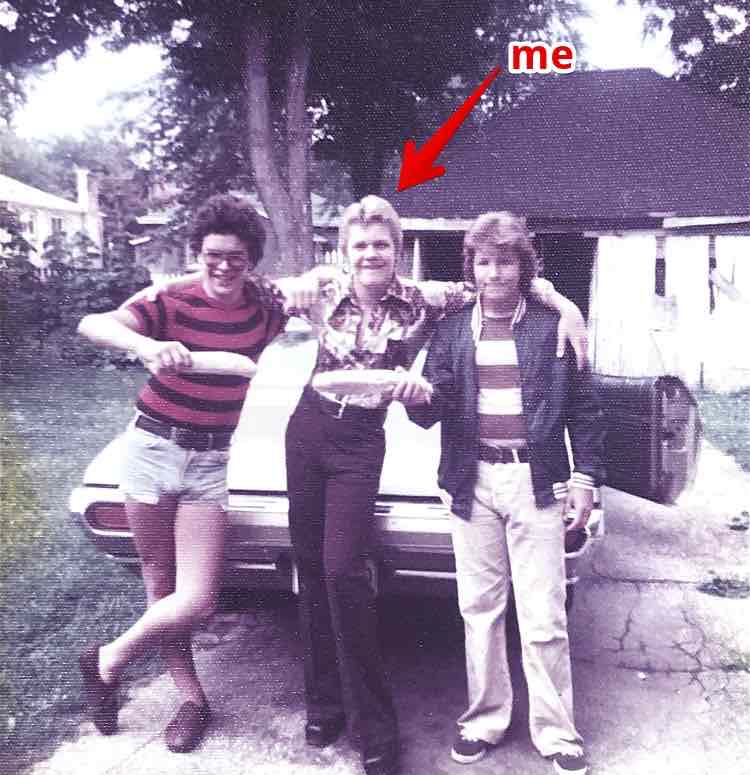

By the end of my career, I was walking around at 260 lbs. But I here’s how I started:

Before there was money involved, and before there any thoughts of earning a living from this “bodybuilding” thing—before all that, there was just the thing itself.

My First Contest

My first bodybuilding contest was in 1983.

I was a third year undergrad at Queen’s University at the time. My mind was awakening through my academic studies and everything seemed possible. The single carryover activity from my youth was working out and bodybuilding training.

With nothing but the magazines to go by for contest prep, I had to work extra hard to make things work. My prep wasn’t very scientific, and there would actually be many consequences to come afterward. But still, I’m immensely proud of it.

I was 100% natural. I kept up my grades. And yes, I won my weight class, the overall in my division, and best poser.

The Prep… Mistakes and All

When I started dieting, I was already in pretty good shape at about 212 lbs. (not sure why, but I have always remembered that number).

In 12 weeks of contest prep I lost over 50 lbs. The lightweight category back then was 155 lbs. and under and I weighed in at 154 lbs. — a bodyweight I hadn’t been since grade 9.

My point is, I really didn’t have 50 lbs.’ worth of fat to lose. As I said, my mindset was that I could outwork everyone. I think I diddo this, to an extent, but I certainly didn’t do everything right.

I’d been dealing with comments from the peanut gallery. I remember guys saying, within earshot of me, “Pff, Abel will never have abs.”

Well, I got it in my head that I was going to show them. That gave me focus.

When I returned to my hometown to compete, having lost all that weight, my own friends didn’t recognize me. Fellow gym rats mistook me for my older brother, and they’d ask my how my younger brother was doing out at university.

I was too naïve at the time to put all this together as a sign that maybeI had taken things too far! Up until the contest I just ignored them, trying to stay focused.

But after the contest, one of my dad’s comments stuck with me.

At my celebration party, my dad pulled me aside. He said, “Scott, I’m happy you won. You deserved it.” He paused, and looked me in the eye, and said, “But the next time I see you looking like that, it better be inside a ****ing coffin!”

That was a moment that stuck with me, especially as I progressed further into the industry and I saw other people suffer the consequences of unhealthy prep after unhealthy prep. Some of them didend inside a coffin.

Anyways, back to the contest.

At the Contest

To give you some perspective, the promoter of this bodybuilding contest in 1983 was a bodybuilder who worked at the Kellogg’s plant. The hot “swag” that every competitor received was…. a box of frosted cornflakes!

I kid you not. At the time, that particular cereal was new on the market, and I remember we were actually thrilled about it. Seriously? Yes, seriously!

There were over 23 lads in my weight class that day. I always remember how for some reason that didn’t faze me: I felt like I’d done the work, but honestly, I just didn’t want to make a fool of myself on stage.

I hit a few poses and things were going “pretty well.”

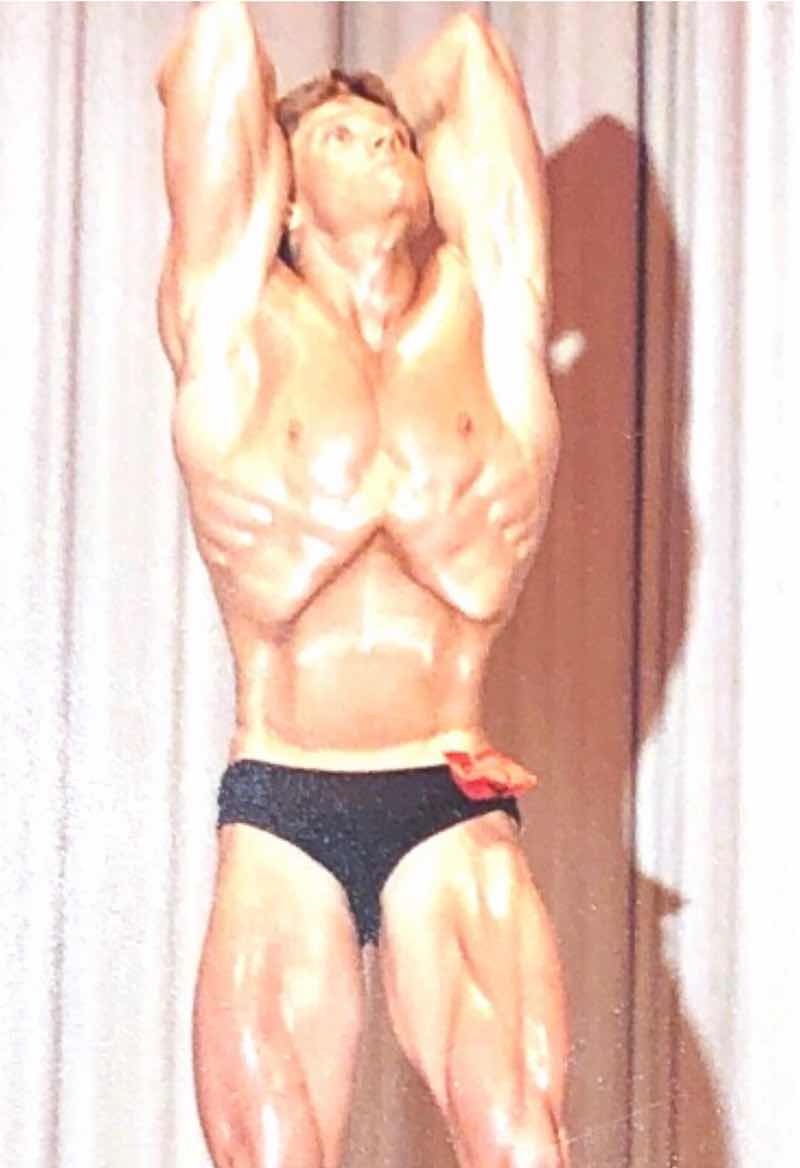

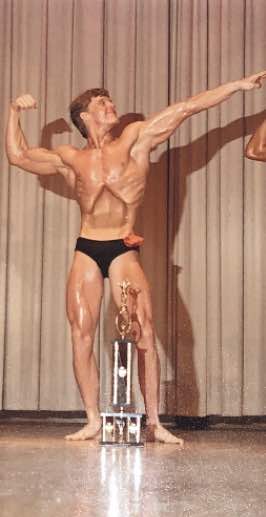

Then I did a stomach vacuum pose. Here it is:

No one else at the contest was doing anything like this to any great dramatic effect. I did mine as slowly and dramatically as I could. I’d gotten the initial idea from Frank Zane’s iconic vacuum pose. I remember practicing it incessantly. (Later, I remember someone asked, “How many days did you go without eating to do that?” Such are the misconceptions and assumptions that float around.)

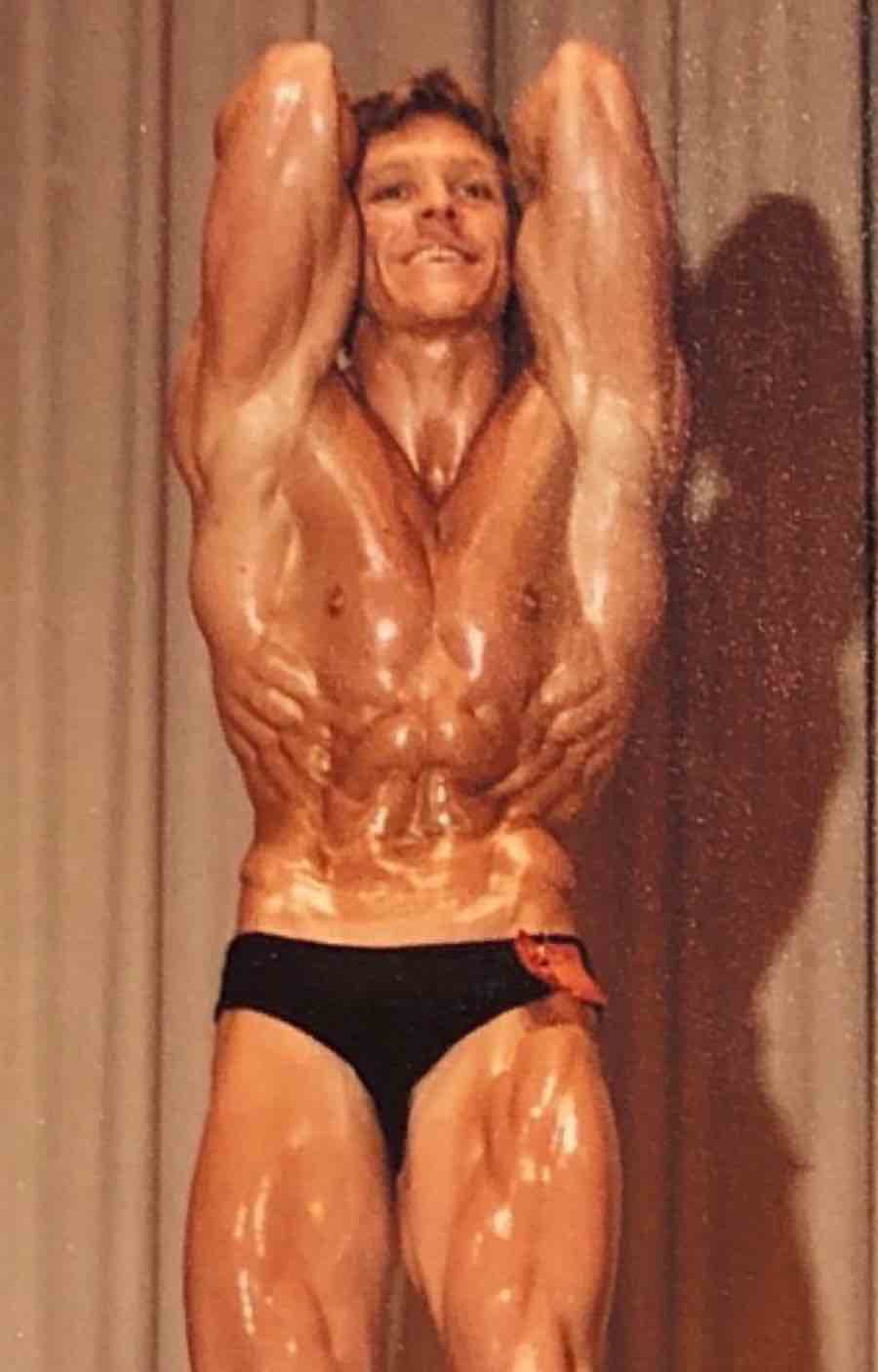

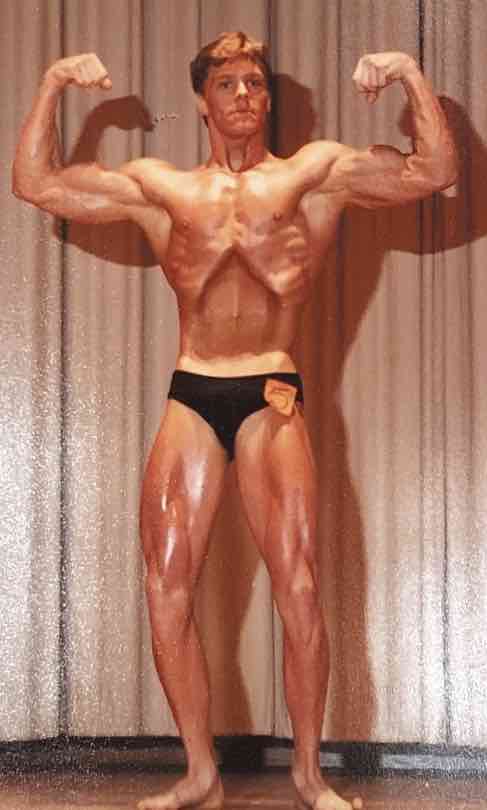

Right after the slow, dramatic vacuum pose I instantly switched to the abdominal pose you see here:

That’s when I knew I’d clinched it. The audience literally jumped to its feet. What a sensation to see and feel a reaction like this, knowing I was creating this reaction myself; that kind of audience response to a performance can be quite addicting let me tell you.

On a personal level, I was most satisfied with the reaction because of those peanut-gallery comments about my abs. Those had been relatively well-known, and much more experienced guys. What they’d said had hurt… but it had also given me incredible focus.

Now, I tend to smile thinking about how those guys had even gotten to me in the first place. In the grand scheme of things, these guys were nobodies, and yet back then, I’d looked up to them. I will say that the kind of self-doubt they created… I never let that happen again. Never.

The Aftermath

As I said, I won my division, the overall, and best posing:

Also, as I said, there was a certain purity to that first contest for me. I did it, as that old Edmund Hillary quote goes, because it was there.

However, the aftermath of the contest surprised me.

There was no social media back then, but in my home town, where the contest took place, the local newspaper did a story on me. And then, back in Kingston where I attended University, both the school newspaper and the local newspaper did a cover story on me.

At the time (and still, to some extent) bodybuilding had as seen as a working-class pursuit. Bodybuilding and higher education didn’t traditionally go together.

Beyond the media, people started tracking me down and asking me for personal help for their own physique transformation. This was before personal training as we know it today was even a thing. Some were calling asking for contest prep help. Some wanted me to choreograph their posing routines for a contest.

Then, the Queen’s Phys. Ed. Department asked me to conduct classes on weight training… and they even PAID me to do it. I mean, my major was sociology, not phys. ed. You can imagine I was a bit surprised. (Didn’t they have professors for that?)

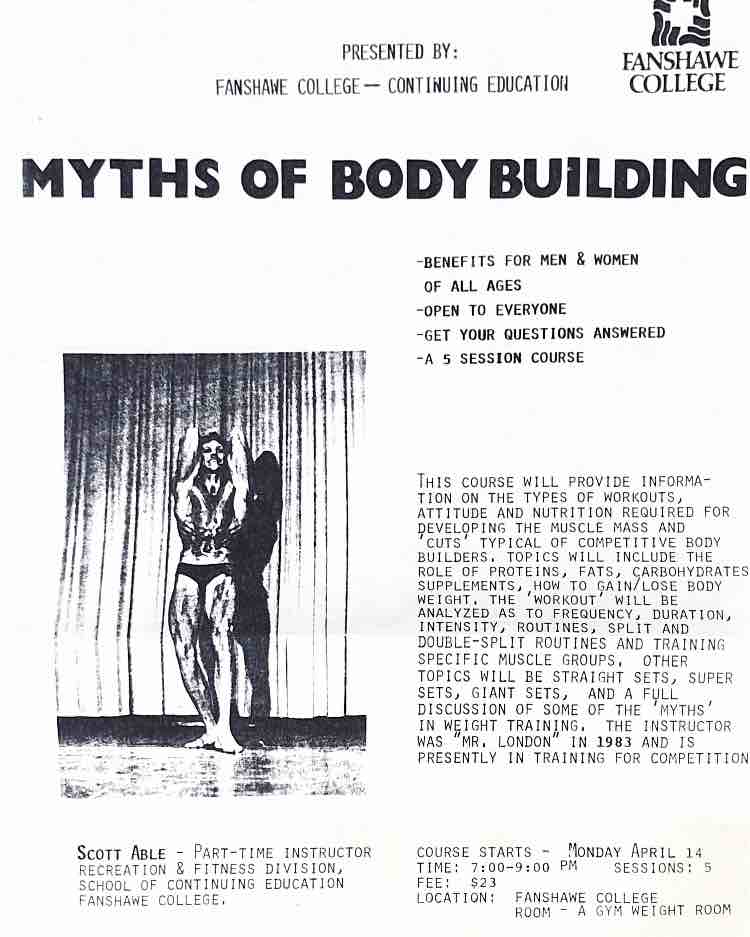

I was also asked to head back to London to Fanshaw College to give lectures on diet and training.

It all seemed so strange to me. All I did was win a contest. But suddenly I was “an expert.”

I also started getting calls from south of the border, in the U.S.. Promoters asked me to compete in their contests. I was asked to give interviews.

And when I returned to London for the summer break I was asked to do an exercise show for cable TV as well.

What the hell was going on?

I’ll tell you what was going. Innocently, and completely by accident, my future career path was opening up. It opened up because I’d invested myself in something I just likeddoing.

I want to stress that this started out in my family’s awful basement at home, right beside the coal furnace room. I remember the whole room smelled like cement dust.

I had an old flimsy metal Weider adjustable bench and plastic weights and a few other primitive pieces of equipment. In winter I had to wear gloves so my hands wouldn’t stick to the metal bars. But I loved it. Again: there was purity to it.

Until recently, if you asked me about many of these old contest photos, I would have scoffed.

But looking through them—experiencing that sense of nostalgia—made me realize what I enjoyed about those initial experiences.

All my really negative memories and associations about bodybuilding are really from the bad taste left in my mouth by the industry, and really, that was all still to come.

Now, I look back and I see how the innocent, naïve, natural bodybuilding me, ended up becoming a lifelong career.

Now, I look back and I feel very grateful and yes, nostalgic, for that time when the world was just opening up to me.